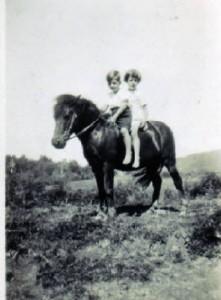

I was six years old before I started school. We could only go three days a week, as there was no bus to take us on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Sometimes when the weather was good we would ride the horses. John and Vincent would double on one horse and I would ride Dandy. We would take a back road that led from our neighbour’s farm, so permission had to be granted to cross their paddocks to get to it. At school there was a spare paddock where we turned the horses loose for the day until time to go home. A few other kids rode to school, but Dandy was the favourite as he was the only Shetland pony there.

It was on my first day at school that I got my hated nickname that Vincent used until I was over sixty years old. It seems I was a skinny kid with long arms and legs. The postmistress had been asked to see me safely onto the bus for home, and as she pushed me up the steps she called out after me “Mind you don’t fall out SPIDER!” Of course the boys were on the bus and heard her, and never let me forget it.

I cannot remember much about school except that we used slates to write on with special slate pencils that made an awful scratchy sound that set your teeth on edge. Also in the playground some of the older boys tried a few bullyboy tricks on the new girls by herding us into the playshed to do whatever they wanted. It did not work with me, they forgot I was brought up with six brothers and could stand up for myself. It was not a big school, there were only two classrooms.

I can remember a school picnic held in the paddock across the road from the school. It must have been some special celebration as everyone was dressed up in their best clothes. I had a lovely shiny new pair of patent leather shoes that hurt my feet if I wore them too long at a time, so I had to take them off to run in the races. There were the usual mixture of these, including egg and spoon, sack race and three legged race. I don’t remember winning any, but I do remember racing and having a lot of fun. Also it was the first time I tasted watermelon, and was so disappointed because it looked so nice and pink and juicy but when I bit into it just tasted watery. I have never had a liking for it since. There was a river running past the paddock and some kids were swimming and I realised it was the same river that passed our farm.

The only other thing I can remember about going to school at Waitomo was that after the first term, we got a daily bus service so there was no more riding horses or days off because of no transport, and the teacher was called Miss Kenyon.